The Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor

WORDS BY THE JUNGLE JOURNAL TEAM

As marine ecosystems face increasing threats from climate change, overfishing, and pollution, transboundary conservation initiatives have become essential. The Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor exemplifies how regional cooperation can protect biodiversity beyond political boundaries. Spanning the waters of Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Panama, this initiative fosters sustainable fisheries, marine protected areas, and legal frameworks to safeguard endangered species like the hammerhead shark. While challenges remain in governance and enforcement, this Corridor stands as a testament to the power of multilateral collaboration in preserving our planet’s interconnected marine ecosystems.

Conservation knows no borders—ecosystems span nations, demanding collaborative solutions. As climate change, biodiversity loss, land degradation, and ocean acidification intensify, international cooperation has never been more urgent. In recent decades, multilateral conservation efforts have gained momentum, reflected in the growing significance of the United Nations Biodiversity summits, held biannually since 1994.

Latin America has followed suit, fostering regional initiatives to protect its rich marine ecosystems. One of the most ambitious efforts is the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor (ETPMC), known as CMAR in Spanish and CMPTO in Portuguese. Established in 1997 and evolving ever since, this transnational initiative has laid the groundwork for a unified approach to marine conservation—one that acknowledges the ecological interconnectivity of the region’s waters and the pressing need for sustainable management.

Spanning a vast triangular expanse—from the Galápagos Islands in the west to Gorgona Island off Colombia’s coast in the east, and north to Coiba Island near Panama—the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor (ETPMC, CMAR, CMPTO) is one of the most biodiverse marine regions on the planet. However, like so many of the world’s ecological treasures, it faces increasing threats. Overfishing, coastal development, tourism, pollution, ocean acidification, and climate changehave placed immense pressure on its delicate ecosystems.

Scientific research has revealed an intricate biological connectivity between the islands of the corridor, with tracking studies of critically endangered hammerhead sharks proving just how interlinked these waters are. Recognizing this ecological reality, Ecuador and Costa Rica initiated the first steps toward a regional conservation agreement in 1997, acknowledging the deep-seated connection between the Galápagos and Cocos Islands. This groundwork led to the landmark San José Declaration of 2004, expanding multilateral cooperation between Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Panama. Since then, the ETPMC (CMAR, CMPTO) has become a model of transnational conservation, bringing together governments, NGOs, and scientific experts to protect this vital marine corridor.

Leatherback Turtle hatchlings, a species of concern, instinctively navigate their way to the ocean by following the slope of the beach, the glow of the moon and stars, and the Earth's magnetic field. Photo by Samantha Trail.

But despite these efforts, overfishing remains the single greatest driver of marine defaunation worldwide, and the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor has been no exception. With the region’s fisheries serving as a major economic lifeline, unsustainable fishing practices have pushed many marine species to the brink. In response to alarming population declines, Panama, Costa Rica, and Colombia launched the Regional Management System for the Sustainable Use of ETPMC (CMAR, CMPTO) Fisheries Resources in 2012. This initiative aims to balance conservation with economic cooperation, reflecting the tension between local fishing economies and the urgent need for stronger environmental protections.

The roots of this crisis trace back decades. In 1982, Costa Rica introduced longline fishing—a technique that indiscriminately captures sharks, turtles, and other marine life—through a partnership with Taiwan. By the late 1980s, Costa Rica’s national longline fleet had expanded to over 500 vessels, with other ETPMC nations seeing similar growth throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The result has been devastating: declining populations of leatherback turtles, hammerhead sharks, and other keystone species essential to the corridor’s ecological balance.

To combat these pressures, the creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) has been one of the most critical state-led conservation measures. Galápagos (Ecuador), Cocos (Costa Rica), Coiba (Panama), and Malpelo and Gorgona (Colombia) are designated MPAs, with all but Gorgona listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. These zones offer refuge from unregulated commercial fishing, yet illegal fishing remains a persistent issue.

Arial view of the Galapagos Islands. Photo credit: NASA

Governance also presents challenges. While the ETPMC nations regulate their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs)—allowing them to enforce conservation laws and establish MPAs—vast stretches of the corridor remain unprotected due to a lack of international regulatory oversight. Since 2018, discussions have been underway to develop a new legal framework for protecting areas beyond national jurisdiction, a crucial step toward securing the future of this fragile marine network.

Among the species at greatest risk is the hammerhead shark—six of the nine known subspecies inhabit the ETPMC’s waters. Over the past 50 years, rampant overfishing has decimated their populations, with the scalloped and great hammerhead sharks now classified in the two highest IUCN Red List threatened categories. The link between population declines and overfishing is undeniable. Yet, conservation measures in recent years have shown promise. In Costa Rica, for instance, the percentage of sharks in total fishing catches dropped from 26.3% in 2006 to just 3.3% in 2010—a hopeful sign that intervention can make a difference.

Ultimately, the artificial boundaries of our political world mean nothing to nature. Ecosystems, species migrations, and marine currents flow freely, demanding cooperation beyond borders. While challenges remain, the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor stands as a testament to what is possible when nations, scientists, and communities work together to protect shared ecological treasures.

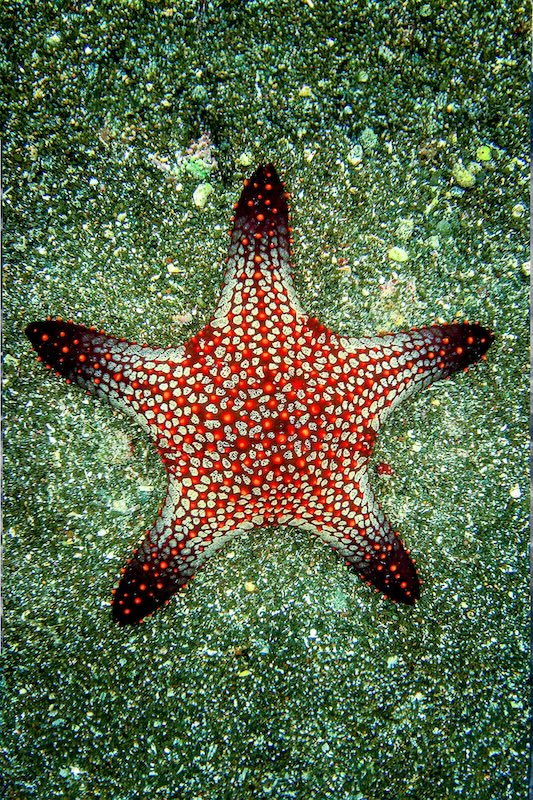

Panamic Cushions (Pentaceraster cumingi) are found in warmer parts of the East Pacific Ocean, including the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor. Photograph by Gary and Donna Brewer.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Subscribe for exclusive insights, upcoming panels, inspiring stories, and opportunities to support communities driving real change.